by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Feb 26, 2015

I used to admire and respect Michael Bowers, Georgia’s Attorney General from 1981 to 1997, but his recent intervention in the debate over the religious freedom bills ought to embarrass him. To be sure, losing my respect won’t cost him any sleep and the mainstream media will only celebrate his move from what it regards as the wrong side of history to the right side. Still, he ought to be embarrassed because the letter he wrote against the House and Senate versions of the bill is a regrettable, albeit entirely predictable, combination of hysteria and inconsistency.

Let’s start with the hysteria. The law, he says, will provide people with an excuse for practicing invidious discrimination and enable every person to justify on the basis of religion becoming a law unto himself or herself. And as if this weren’t bad enough, Bowers invokes the spectre of the KKK returning fully garbed in hoods, a practice he alleges might well be protected by the proposed Georgia legislation.

Well, no, no, and a thousand times no.

In the first place, Bowers doesn’t actually argue that the law permits invidious discrimination; he merely asserts the following:

The proposed RFRA is nothing more than an effort to legalize discrimination against disfavored groups, requiring only the discriminating party’s assertion of a burden on his or her…purported religious belief.

I’ll explain shortly why this is an extremely misleading “explanation” of what the bill will do, but, for now, I’ll restrict myself to recounting how he reaches this conclusion. It’s all, he says, in the timing. If the Georgia legislature had taken seriously the threat to religious liberty that came from the Supreme Court’s decision in Employment Division v. Smith, why did it wait more than twenty years to do so? The answer can only be “same sex marriage.” Religious liberty is simply the fig leaf behind which those who want to deny gays and lesbians marriage equality (not to mention other sorts of equality) are going to try to hide.

I agree that timing is an issue, but not in the way Bowers insists. There is a new sense of urgency, not about protecting people’s “right” to discriminate, but rather about protecting traditional religious belief and practice from aggressive attempts to use state and judicial power to force people to conform to the new order. Some of these threats were, well, not quite unimaginable but barely on the horizon as recently as just a few years ago. Remember pro-life Michigan Democratic Congressman Bart Stupak, who supported the Affordable Care Act in exchange for an executive order reaffirming that no federal funds would pay for abortions? Just a few years later, the contraception mandate enforced by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services violated that promise, according to a rueful Stupak. Student religious organizations have effectively been run off college campuses (not everywhere, to be sure) because they require that their officers actually share the principles of the organization. And yes, businesspeople who in other instances have been quite happy to serve their gay and lesbian customers have sought to draw the line at providing services to same-sex wedding ceremonies they don’t and can’t conscientiously support. Traditional religious believers can be excused for feeling more than a bit threatened by all these developments and thinking that more robust religious liberty protection is required.

Let me turn now to the “law unto himself or herself” canard. Here’s Bowers’ best explanation of this claim (oddly in the section of the letter supposedly devoted to his contention about invidious discrimination):

Any time a person wished to refuse to act in response to a government requirement, he or she could assert the protection of the proposed RFRA. Whether legitimate or not, a controversy would likely ensue involving law enforcement officials, school officials, hospital administrators, or other government officers, and possibly the courts. The potential undermining of the rule of law is limitless.

It seems to me that this contention proves too much, as anyone could make the same claim about the First Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment due process clause. Does Bowers want to throw those out too, as they certainly can serve as bases for an individual refusing “to act in response to a government requirement”? The point that Bowers doesn’t ever really concede directly is that a RFRA claim isn’t an automatic trump against government action or regulation; it merely demands that government articulate a compelling state interest and that the measure proposed be the least restrictive means to achieve that interest. These questions are for a judge to decide, and the individual resisting the law or regulation may not win. The interest could indeed be compelling, as I assume prohibiting genuinely invidious discrimination might be, and the means chosen could be the least restrictive possible. The RFRA merely offers religious believers a recourse in the event that the proverbial tyrannical majority (about which James Madison worried in Federalist #10) decides that the shortest route between two points is a straight line through religious freedom. Indeed, by assuring that the law in the largest sense protects the rights government is “ordained and established” (the words of the Declaration of Independence) to protect, a RFRA actually serves to maintain public confidence in the rule of law.

And then there are the hooded knights of the KKK, which amounts to pure fear-mongering on Bowers’ behalf, something that ought to have been entirely unworthy of a former Attorney General. Given Georgia’s history, if anything is a compelling state interest, it’s keeping the KKK from hiding behind hoods as it spews its hatred.

And again—it bears repeating, since Bowers so frequently encourages misunderstanding—whether a RFRA claim stands depends not upon the individual asserting it, but upon the judge hearing the case. Of course, Bowers has to acknowledge this point, but he attempts to deprive it of its force by making what judges will do seem altogether unpredictable:

It is impossible to anticipate whether Georgia courts would follow the lead of the Eleventh Circuit and interpret the RFRA as co-extensive with First Amendment jurisprudence or whether the courts would treat RFRA as ushering in a new era of religious freedom jurisprudence that strikes down neutral laws of general applicability based on an alleged burden on the exercise of religion.

All he has is this uncertainty about what courts will do. He has to concede that other courts—state and federal—have most emphatically not permitted the parade of horribles with which he has regaled us in the letter. Indeed, one of the best reviews of our state and federal RFRA experience suggests that we have little or nothing to worry about and, indeed, much to which to look forward.

Let me conclude by offering one note of agreement with Bowers’ argument. I also worry about what judges might do, especially where religious freedom is concerned. I don’t want what some have called our first freedom to depend upon what might be the whim of a magistrate. To be sure, I try to have as high an opinion as possible of our state and federal judges, but have to confess that I have been disappointed more than a few times by their decisions and the quality of the reasoning in support of them. I wish it hadn’t come to this. I wish that popular and legislative majorities were always respectful and solicitous of the rights of those who seem to stand in their way. I wish that righteous and self-righteous indignation didn’t all too often get the better of us. I wish that we were more frequently visited by “the better angels of our nature,” as Abraham Lincoln so eloquently put it in his First Inaugural. I pray for all of this, but I’m also going to urge my representatives to vote for these pieces of legislation.

Dr. Joseph M. Knipperberg is a contributing scholar at the Georgia Center for Opportunity and Professor of Politics at Oglethorpe University.

Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Georgia Center for Opportunity.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Feb 24, 2015

It’s official. Governor Nathan Deal signed an executive order on February 23rd to “ban the box” on applications for state employment in Georgia. This order will remove the question about felony convictions from the initial job application and postpone it to a later point in the hiring process. This policy is intended to provide those with a criminal record a fair shot at showing employers why they are the best candidate for a job without being automatically screened from the hiring process simply because they have a felony conviction.

The Governor laid out specific hiring practices that government entities of the State of Georgia shall follow:

- Prohibit the use of a criminal record as an automatic bar to employment.

- Prevent the use of an application form that inappropriately excludes and discriminates against qualified job applicants.

- Promote the accurate use and interpretation of a criminal record.

- Provide qualified applicants with the opportunity to discuss any inaccuracies, contest the content and relevance of a criminal record, and provide information that demonstrates rehabilitation.

- Require initial disclosure on applications for sensitive governmental positions in which a criminal history would be an immediate disqualification.

Georgia is joining thirteen other states who have implemented a fair hiring policy and is the first state in the South to do so. This policy will help to remove a barrier to employment for those with a criminal record by opening up more job opportunities for which motivated returning citizens may be qualified. The state is setting the example for how county, city, and private employers could aid people leaving prison in the reintegration process by giving them a fair shot at jobs for which they are good candidates.

Georgia Center for Opportunity (GCO) applauds the important step taken by the Governor to “ban the box” as well as the efforts of all those who have been involved in working to increase employment opportunities for returning citizens in Georgia. In December 2013, GCO published a report recommending that the state “ban the box” and set the example for private employers by hiring and maintaining qualified returning citizens as employees. This recent executive order is the first step in seeing this fulfilled.

In addition, GCO is pleased to see several other recommendations from our December 2013 report currently being considered by the General Assembly or state agencies. These recommendations include offering a State Work Opportunity Tax Credit to incentivize employers to hire returning citizens, lifting professional license restrictions for those with felony convictions, and ensuring identification is secured prior to a person’s release from prison.

As Georgia continues to take positive steps forward in removing barriers to opportunity among those involved with the criminal justice system, the public should begin to see more examples of returning citizens who are not only making it in society, but flourishing.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Feb 23, 2015

Attempts at reforming the public education system in Georgia are not new. Even just looking over the last 20 years, numerous reform efforts have been introduced as a means to improve educational outcomes among the state’s youth. Some of these ideas have had a better effect than others, yet as a whole they have not achieved the level of progress Georgia has hoped for. While modest gains have been made in the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores for eighth grade students and the graduation rate for high school students has risen since 2002, Georgia still has a grade of C-Minus overall and one of the lowest graduation rates in the country.

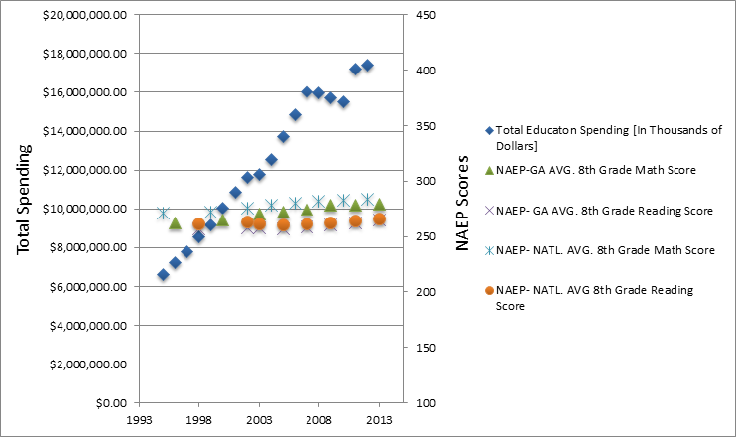

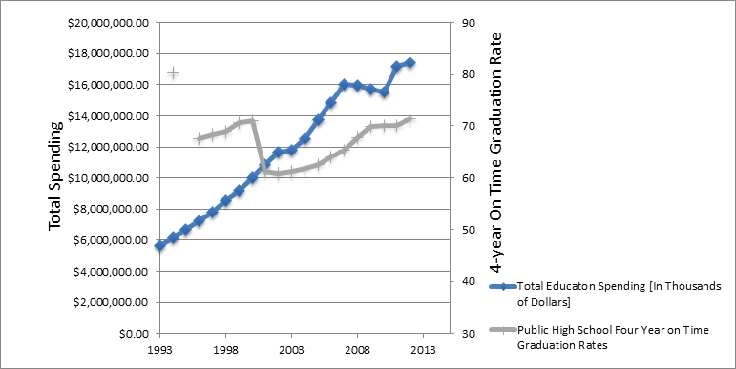

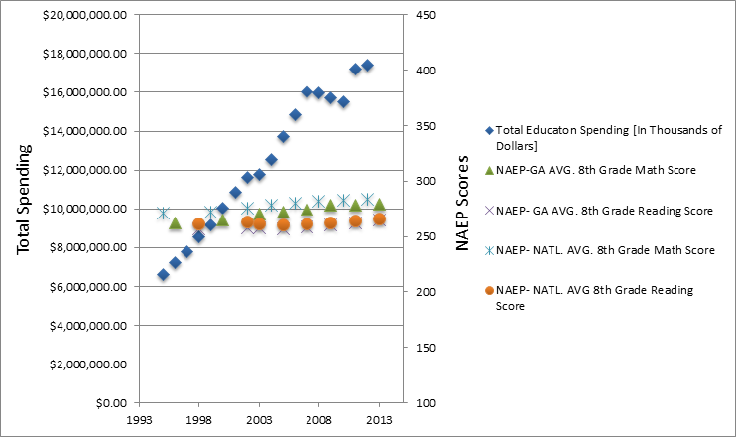

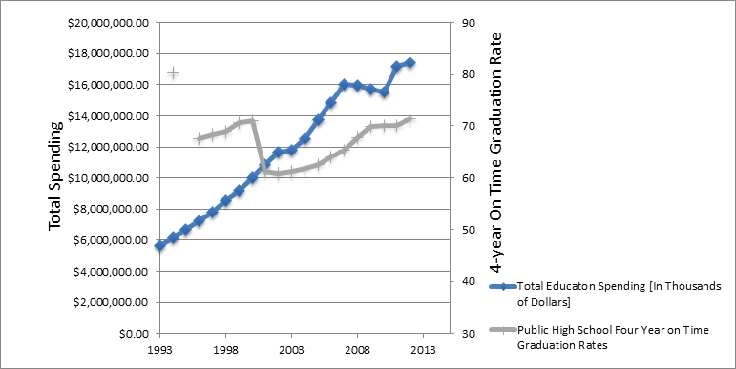

Below is a list of reforms that Georgia has tried since the introduction of the Hope Scholarship and the charter school law that was passed in 1993. Comparing these reforms to the two graphs that follow demonstrates that achievement among Georgia’s eighth grade and high school students has been relatively stagnant compared to the amount of money spent to improve education over the last two decades.

Past Reforms

1993 – HOPE Scholarship created and funded by lottery. Charter school law passed; only public schools can convert to charters; commissioned by local and state board.

2000 – A+ Education Act mandates end-of-course assessments and Criterion-Referenced Competency Test (CRCT) in core subjects.

2001 – No Child Left Behind and Title I grants public schools with high percentages of students receiving free or reduced lunch additional federal funding.

2005 – Georgia Performance Standards implemented as a result of Quality Core Curriculum (QCC) reform to align with national standards.

2008 – HB 881 creates the Georgia Charter Schools Commission. Qualified Education Expense (QEE) Tax Credit Bill passed (HB 1183).

2009 – American Recovery Reinvestment Act; Georgia received almost $2 billion dollars to invest in education. HB555 requires local schools systems to grant charters within the district access to unoccupied buildings at no cost.

2010 – As a result of Common Core State Standards initiative, Georgia adopts new content standards in language arts, math, science, and social studies.

2011 – HB881 Georgia Charter Commission declared unconstitutional; 16 charters, 15,000 students impacted. QEE Tax Credit Bill amended (HB 325) creating student scholarship organizations (SSOs); individual and corporate taxpayers can contribute to SSOs in exchange for a state tax credit.

2012 – Amendment One passes and Georgia Charter Commission is reinstated. College and Career Performance Readiness Index (CCPRI) conducted “study year” of public schools’ performance.

2013 – Tax Credit Bill amended (HB283); cap increased to $58 million. Career Clusters curriculum implemented in schools.

2014 – Students are to take Georgia Milestones instead of CRCT and EOCT. Charter schools reach a total of 315.

- 77 start-ups

- 31 conversions

- 207 charter system schools

- 16 charter systems

- 13 state commissioned specialty schools

- 13.5% of total student population

Total Spending vs. NAEP Scores

Total Spending vs. High School Graduation Rate

It seems that Georgia will have to do something different than what has been attempted thus far if we want to experience real gains in educational outcomes among K-12 students – something different than pumping more money into the current system, aligning state curriculum to national standards, or allowing only a limited number of parents and students school choice. We need greater options that ensure tax dollars are well spent and students’ educational needs are met. Only then will be begin to see a more dramatic increase in the number of high school graduates who are ready for college, career, and life.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Feb 12, 2015

The Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform (CJRC) released their latest report this past Friday (Feb. 6th) with recommendations aimed to increase public safety, hold offenders accountable, and reduce recidivism in our state. This is the fourth consecutive report that the CJRC has produced since 2011 after being tasked by the Governor and the General Assembly to develop a smarter, evidence-based approach to criminal justice in our state.

As reflected in the report, a major focus of the CJRC and the Governor’s Office of Transition, Support and Reentry (GOTSR) in 2014 was to develop a comprehensive approach to reentry so that every person leaving prison has the tools and support they need to succeed in the community.

To aid in the development of this approach, the Council and GOTSR partnered with the Michigan-based Center for Justice Innovation and reentry expert Dennis Schrantz to produce the Georgia Prisoner Reentry Initiative (GA-PRI). The GA-PRI is a five-year plan based largely on the evidence-based policies practices laid out in the 2005 Council of State Governments’ Report of the Re-Entry Policy Council and the 2008 National Institute of Corrections’ Transition from Prison to the Community (TPC) Reentry Handbook, but tailored specifically to meet Georgia’s reentry needs.

Georgia’s reentry team pursued federal funding to implement the GA-PRI in 2014, highlighting its “one strategy, one plan” philosophy that aims to unify planning and implementation of evidence-based practices among agencies and stakeholders. The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) welcomed the smart plan and awarded Georgia four grants which totaled $6 million. Georgia’s strategy is now being featured by the BJA at training events across the county.

Details and recommendations related to the GA-PRI can be viewed in this report, as well as the complete three-year implementation plan which is located in the addendum.

Other key pieces of the report include recommendations in the following areas:

Adult System

- Restore the intent of the Georgia’s First Offender Act

- Improve pre-trial diversion alternatives for certain offenders

- Extend parole eligibility for certain qualified nonviolent, recidivist drug offenders

- Extend sentences for offenders whose probation has been revoked and who wish to participate in a felony accountability court program

Juvenile Justice System

- Improve the collecting and sharing of electronic data throughout the juvenile justice system

Misdemeanor Probation System

- Address deficiencies and improve transparency and fairness in misdemeanor probation services

At GCO, we are particularly happy to see the following recommendations in the CJRC’s report which aim to increase employment opportunities for returning citizens:

- Establish licensing policies that ensure returning citizens have appropriate opportunities for licensing

- Explore opportunities for a state work opportunity tax credit to incentivize offering employment to returning citizens

- Revamp prison work details to provide experience that meets the requirements of Prior Learning Assessments (PLAs) so technical college credits can be awarded for work experience gained on prison details

- Explore resources available to purchase and deploy a Department of Driver Services (DDS) mobile unit to process state IDs at state correctional facilities

Read the full report here and visit the newly created website for the Governor’s Office of Transition, Support and Reentry.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Feb 11, 2015

Georgia’s public school system is failing many of our children, and it seems everybody has an opinion in regard to what needs to happen. But one truism has become apparent: More money is not the solution.

Nationally, spending on public education in constant dollars has nearly tripled since 1970, and the expenditures per student have doubled from $4,500 per student per year in 1970 to almost $11,000 today.[1] During this same time period, the National Average for Educational Progress (NAEP) scores for 17-year-olds have remained essentially unchanged. Americans spend more money per-student than any other nation in the world while only performing in the middle-to-back of the pack among developed countries.

While an increase in spending has not yielded higher achievement scores among U.S. students, it has been successful in accomplishing one thing: increasing the size of school administration. Since 1950, the overall number of school administrators in the U.S. has risen by a staggering 702 percent, while the number of teachers has only grown by 252 percent, and the number of students has increased by only 96 percent.[2] For all this growth in school administration and faculty, the outcomes in student achievement have been disappointing.

The same can be said for Georgia. Spending on public education increased drastically from $5.6 billion in 1993 to $17.4 billion in 2012, yielding an improved student-teacher ratio during this time period (16.7 in 1993 to 15.6 in 2012). Yet despite all this spending and having more teachers and smaller classroom sizes, NAEP scores for eighth grade students in Georgia remained virtually the same. Similarly, the high school graduation rate did not improve significantly during this time period, going from 67.6 percent in 1996 to 71.5 percent in 2012, while hitting a low of 60.8 percent in 2002.

Both in Georgia and nationally we continue to operate under the assumption that more money and more staff will solve the problem of a failing educational system. However, statistic after statistic indicates that pouring more money into Georgia’s failing public school system will not provide any substantial improvement, especially for Georgia’s most vulnerable children. There have, and continue to be, serious and well-intentioned efforts to reform the system. But because these reforms only provide minor changes to the system without seeking to change the way the system is organized, they limit themselves to minor improvements in standardized test scores.

In order to improve the educational opportunities we give Georgia’s children and ensure that the money spent on public education is not wasted on poor results, Georgia needs a new and innovative approach to education – an approach that gives parents the power to see their children succeed in education and in life. We need quality instruction that meets the needs of an enormously diverse group of students in a broad range of circumstances.

This just might be the power that newly proposed Education Savings Accounts offer.

Notes

[1] McShane, Michael. How America’s Education System Fails to Live Up to Its Promises (Washington, DC: AEI Press, 2015).

[2] Ibid.